KZP - A simple yet deep logic puzzle

I’ve always been fascinated by puzzles such as sudoku and hashi (bridges). Sometimes, you get a really beautiful chain of deductions leading to an unexpected ‘a-ha!’ moment. Those moments, in my opinion, are the reason to solve puzzles in the first place.

For quite a while, I’d been trying to create my own puzzle that I could enjoy as much as more famous logic puzzles. Somehow this puzzle came to me completely by accident. I happened to be flicking through a magazine, bored, when I flipped past the answers page to the puzzles in that issue. Having not seen the puzzles, I entertained myself trying to reverse-engineer the rules from the solutions given. Needless to say, none of my ideas were even close, but one of my interpretations ended up being worthy of further exploration. I drew out a random board and tried to solve it. Surprisingly, it worked very well, and I’ve kept solving them every so often until this day.

The Rules

You can try the puzzle yourself here.

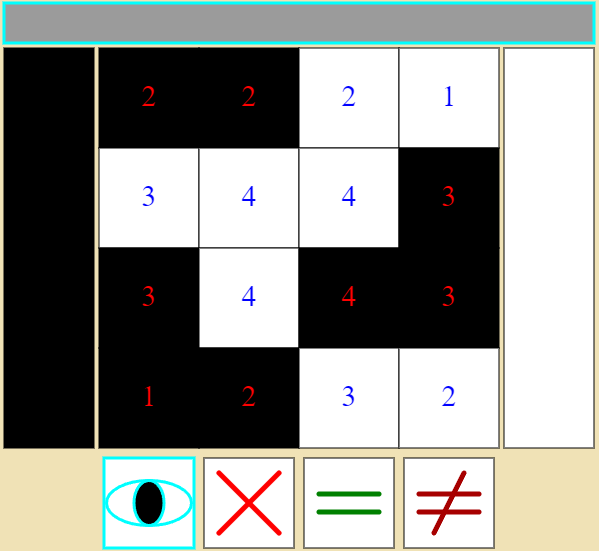

It’s easiest to understand the rules if you look at a solved board and work backwards. Here’s an example of a typical board:

You can see that in the solved board, every square is either coloured black or white. Here’s the core rule:

the number in any given square counts how many of its neighbours (including diagonals and the numbered square itself) are of one particular colour.

For example, the 1 in the top right corner is asserting that out of its three neighbours and itself, there is one square of one colour (in this case black), and therefore three (four neighbours - 1) of the other colour (white). The three right beneath it states that out of its six neighbours (including itself), three are black, and the other three are white.

The important thing to note here is that two different squares can be ‘counting’ different colours. There is no correlation between what a square is counting and what colour it actually is.

Finally, you may have noticed how the solution colours (red and blue) do not match up with the paint colours. This is because it’s actually impossible to tell which is which from the numbers alone. You can still determine the regions, however. As long as your solution has a consistent map between the red/blue numbers and the black/white paints, it’s a solution. In other words, if one red square is painted black, all the other red squares must be painted black too.

Website Interface

You might have noticed the equals and not equals buttons at the bottom of the puzzle. These two tools are your best friends when it comes to solving. They simply mark relationships between squares you don’t yet know the colour of. Sometimes you’ll figure out that two squares must be the same colour, even though you don’t know what that particular colour is. In that case, you can click the equals, and then the two squares (which currently have to be adjacent to display the relationship). In exactly the same way, if you can tell two squares are opposites, then you use the not equals button.

Finally, the eye toggles whether to display the solution, and the cross removes all the relationships that have been drawn.

Example Solving Walkthrough

Here is a nice and easy puzzle to start with. We’ll go through it step by step. I won’t include images to minimise spoilers, and I encourage you to try figure out things yourself before reading this guide.

Coordinates will be given as (x,y), with the top left corner being (0,0), and the bottom right being (3,3).

- Notice the two zeroes in the upper left? They’re saying that 0 of their neighbours are one colour, and hence all of them are the other colour. Since we haven’t painted any tiles yet, paint that entire 3x2 rectangle of neighbours white.

- See the 1 in the bottom left corner (0,3)? It’s saying that exactly one of its neighbours is one colour, and all the others are the other colour. Now, if you did step 1 correctly, the two squares above it should be white. Clearly, this can’t be counting white neighbours, because it already has more than one. We can conclude that one of the two unpainted squares {(0,3) and (1,3)} must be black, and the other must be white. We can use the not-equals button to keep track of this.

- Let’s look at the 1 in (1,3). This is saying that, once again, exactly one neighbour is of one colour, and the others of the other colour. Again, this must be counting blacks, as we already have more than one white neighbour. Additionally, we know that one of {(0,3) and (1,3)} must be black, so this square already has its one black neighbour (although we don’t know which of the two squares it is yet. This means, then, that neither {(1,2) and (1,3)} can be black, as that would give us more than one black neighbour. Hence, they must both be white.

- Let’s move on to the 1 at (1,0). In the same way as before, it should have one black neighbour, and so one of {(2,0) and (2,1)} are different. Mark them with the not-equals tool like before.

- Now, look at the 3 at (2,0). This says that 3 of the 6 neighbours are one colour, and the other three are the other colour. Threes on the edge are nice, because they give us this 50/50 split. In this case, we know that {(1,0) and (1,1)} are both white, and that one of {(2,0) and (2,1)} is also white. Therefore, the other three squares have to be black. The fact that one of {(2,0) and (2,1)} is black tells us nothing new, but now we know that {(3,0) and (3,1)} are black. Colour them in.

- We’ll move on to the bottom right corner (3,3). We can figure out it’s touching one black, so one of {(3,2) and (3,3)} must be black, and the other white. Mark them with the not-equals tool.

- Let’s look at the 1 at (2,3). Thanks to step 6, we know that one of its neighbours on the right is black, which satisfies its count. Therefore, (1,3) must be white, and because of the mark we made in step 2, we can conclude that (0,3) is black.

- Look at the 2 at (3,1). We know that it must be counting whites (see if you can figure out why). Since one of {(2,0) and (2,1)} is white, and it’s already touching another white, (3,2) must be black.

- Finally, Let’s look at (3,2). You should be able to finish easily from here. When you’re done, hit the eye to check that the colours match up.

A Note on Solvability

The puzzles for the site are all randomly generated. Sadly, not every puzzle has a unique solution. One common pattern that frequently ends up unsolvable is a checkerboard 2x2 corner with a four diagonally touching its corner. If you meet one of these ones with a different pattern, I’d love to know about it! Feel free to contact me.